China has successfully launched its Chang’e 4 spacecraft toward the moon, a daring mission to land on the lunar farside for the first time in history.

The launch took place from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in Sichuan Province on a Long March 3B rocket today, December 7, at 1:23 pm Eastern time (2:23 am local time in China). The spacecraft will now begin a three-day journey to the moon before remaining in polar lunar orbit until a landing attempt is made by the end of the year at the earliest. “They are talking about around December 31 or January 1,” says Bernard Foing, director of the European Space Agency’s International Lunar Exploration Working Group, who was part of a European collaboration with the China National Space Administration (CNSA) on the mission. So far, the spacecraft appears to be in good health.

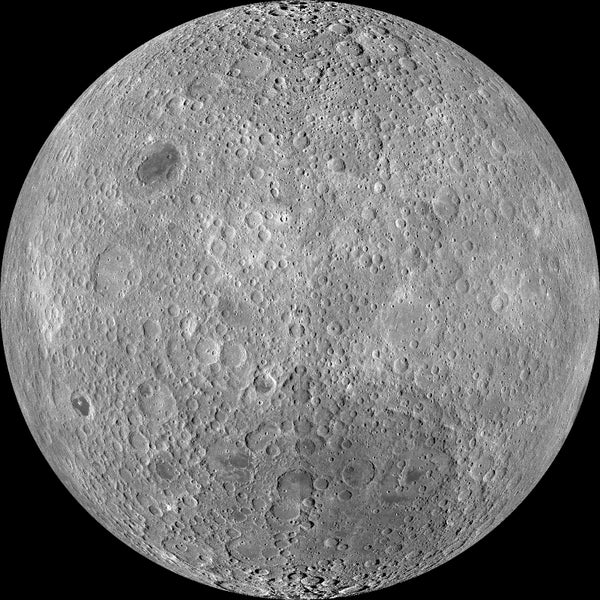

China will use the preceding three weeks in lunar orbit to take images of the surface, and ensure the landing site is clear of obstacles. Whenever it occurs, the seven-step landing process—which will be entirely autonomous—will last just 11 minutes from the deorbit burn to touching down on the surface. Chang’e 4 is intended to land in the 186-kilometer-wide Von Kármán Crater in the South Pole–Aitken Basin on the moon; the latter feature is the moon’s largest-known impact crater at about 2,500 kilometers across. This scientifically fascinating region could yield invaluable data about how the moon formed and evolved, owing to exposed mantle at this location.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Although located near the moon’s south pole, Chang’e 4’s target crater is still subjected to extreme temperature changes as the moon rotates once every 28 days. The crater experiences about 14 days of sunlight with average temperatures up to 110 degrees Celsius, before plummeting to some –173 degrees C for about 14 days of night. These temperature swings proved too much for Chang’e 4’s predecessor, Chang’e 3, which landed on the moon on December 14, 2013. The two missions are almost identical in design; the former was originally built as a backup for the latter. Both include a large lander weighing about 1,200 kilograms, and from this a smaller rover about one meter across and weighing 140 kilograms is deployed on the lunar surface.

But the key difference this time is Chang’e 3 landed on the moon’s nearside that always faces Earth. Chang’e 4 will instead head for the farside, long seen as a scientific milestone for lunar exploration. “A farside landing is a big deal, because nobody’s ever done it,” says Roger Launius, NASA’s former chief historian. A major challenge, however, is the farside is never in sight of Earth, making direct communication impossible. So in May 2018 China launched a relay satellite called Queqiao to a gravitationally stable lunar synchronous orbit about 65,000 kilometers beyond the moon, where the gravity of both Earth and the moon keep the relay satellite moving in a halolike motion that ensures it is continuously in sight of both the lunar farside and Earth. All communication with the lander and rover must be relayed via this satellite.

Onboard the Chang’e 4 mission is a suite of instruments primed for a diverse series of scientific studies. It includes a ground-penetrating radar to look up to 100 meters beneath the surface, three cameras, radio astronomy experiments to study the Milky Way unhindered by Earth-based interference and an intriguing experiment to grow biological samples on the lunar surface. Also onboard are two European-led experiments, one from Christian Albrechts University of Kiel in Germany and another from the Swedish Institute of Space Physics, which will study cosmic rays and solar wind hitting the surface. European scientists also helped China choose the Chang’e 4 landing site.

It is unclear how long the mission will last, but Foing says China expects the rover to endure for at least one Earth month—which includes one lunar day and night. The landing is scheduled as close to the start of lunar day in the region as possible, which begins on December 30, giving the rover ample sunlight to feed its solar panels. The lander could survive much longer, though; whereas the Chang’e 3 rover died after a single Earth day, its lander is still operational today after more than five years.

Even if it survives just a single Earth day, this farside mission will be historic. “You’re opening up half a world that wasn’t accessible before,” says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. If it all goes well, China hopes to return samples from the moon in 2019 and 2024 with Chang’e 5 and Chang’e 6, before ultimately landing human explorers there.